Migration Financing: Filling the Missing Market with Income Sharing Agreements

A World Where Opportunities Are Not Constrained by Birthplace

Tl;dr

1. The financial market for migration could potentially accommodate 10-20 million migrants annually, which implies a market with $3-12 trillion in outstanding issuance.

2. Income-sharing agreements (ISAs) could provide a solution by offering the necessary financing to prospective migrants.

3. The ISA migration market is large enough to require asset-backed securities (ABS) to optimize balance sheet usage and efficiently manage risk.

4. Private businesses, governments, development banks, international organizations, and ethical business practices all contribute to constructing a market at scale.

5. The labor market mismatch between Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs) and High-Income Countries (HICs) represents a substantial lost economic opportunity.

6. Significant barriers to migration, such as high costs and complex immigration systems, keep migration rates lower than desired.

7. ISAs align the incentives of lenders and borrowers, with repayment being contingent on the borrower's future income.

The Market for Financing Expenses Related to Migration is Unfulfilled

Shifting global demographics suggest a forthcoming era of large-scale migration. Facilitating this requires significant financial support, yet the landscape of this potential market remains largely unexplored. In this essay, I estimate the market's potential and propose a lending structure to unlock the economic benefits of global migration.

High-income countries (HICs) offer more economic opportunities than low and middle-income countries (LMICs). While HICs face labor shortages across skill levels, LMICs have abundant qualified individuals without adequate job opportunities. This mismatch in labor markets leads to lost economic potential. Barriers like language training costs, legal fees, and complex visa processes hinder migration, keeping rates below HIC employers' and LMIC workers' preferences.

Facilitating migration flows needs novel solutions. ISAs, an overlooked financing model contingent on future income, represent a potential solution for facilitating migration. ISAs could provide the necessary financing to overcome prohibitive migration costs for motivated individuals from LMICs. Migration would maintain dependency ratios in HICs facing labor shortages while expanding opportunities for migrants from LMICs. Realizing this potential, however, requires coordinated efforts between governments, financial institutions, employers, and developmental bodies.

By facilitating the movement of willing migrants, we can unlock a potential market of 10-20 million individuals annually1. With typical migration costs estimated at €10,000 to €30,000 per person, this represents an annual market requiring €300-600 billion in financing. Asset durations might be 10 to 20 years, implying the total outstanding market for migration financing could reach €3-12 trillion, comparable to other major asset-backed securities markets2. Harnessing this market can catalyze global economic growth and improve millions of lives.

Understanding ISAs

Income Share Agreements, or ISAs, attempt to be equitable financial contracts. Unlike traditional loans accruing interest, ISAs involve an investor providing an individual with upfront funds. In return, the individual commits to repaying a fixed percentage of their future income. Many find it helpful to think of this as owing a fixed number of repayments instead of a fixed number of dollars or euros. Then, the magnitude of the repayment is matched to the borrower’s ability to pay.

The foundational elements of any ISA contract include:

Initial Funding Amount: The upfront sum provided to the individual.

Income Share Percentage: A fixed annual percentage of the borrower's income owed to the investor.

Payment Term: The set duration for repayments, with any balance post-term being forgiven.

Income Threshold: A specified income level that triggers repayments. Earnings below this exempt the borrower from that year's payment.

Payment Cap: The total maximum repayment amount, which, once met, concludes the ISA obligations.3

To illustrate, an individual funded with 28,000 euros could be obligated to repay 14% of their income when they earn above 27,000 euros, for up to ten years or until they've paid a total of 56,000 euros.

A notable instance of a successful ISA program is the Studierendengesellschaft Witten/Herdecke (SG) in Germany, which has been operational since 1995. From what I understand, SG pioneered a comprehensive set of best practices for ISAs, which have since been emulated in various German initiatives4. The long track record shows how direct costs, such as education or migration, are met while balancing the borrower's aspirations and the investor's risk considerations.

Applying ISAs to Migration Financing

When tailored to the challenges of migration, ISAs open up transformative possibilities. The 'Initial Funding Amount' can be structured to cover vital migration expenses: language courses, educational credentialing, legal facilitation, and even travel.

One of the unique features of ISAs in the migration context is that they can incentivize the investor to provide additional support to the migrant beyond the initial funding amount. This could include help with job placement, language training, or legal assistance. Since the investor's return is directly tied to the migrant's future income, it is in the investor's interest to ensure that the migrant is successful in their new country.

Moreover, ISAs afford migrants the liberty to navigate the job market freely. This is a distinct advantage over contractual migrant worker programs, which often impose strict restrictions on job mobility. With ISAs, migrants can explore different occupations and switch jobs as needed, tailoring their career paths according to their goals and circumstances.5

Ethical Migration Financing

Over time, the ISA community has built ethical structures for issuance6. Similarly, consensus on what constitutes ethical practices in economic migration is forming7. Given the potential power dynamics between a migrant and employer or between a borrower and lender, it's imperative to adhere to best practices to champion fairness.

An integrated framework of oversight bodies is essential to drive the desired outcomes in ISA-based migration financing:

Regulatory Agencies: These would formulate and enforce the legal paradigms governing ISAs. Their mandate is setting clear boundaries for ISA parameters, like capping maximum payment values, determining repayment durations, and establishing minimum income thresholds.

Industry Associations: These bodies disseminate best practices, facilitate knowledge exchange, and ensure the adoption of ethical conduct standards, often exceeding the regulatory minimums.

Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs): NGOs oversee lender and employer actions, champion the rights of migrants, and proactively offer resources to those in need.

By working together, these supervising bodies create an environment ensuring the ethical use of ISAs and the fair treatment of migrants. This protects the rights and interests of individuals and contributes to the overall health and sustainability of the migration financing market.

Ethical Labor Migration

Income-sharing agreements can catalyze migration, but it's paramount to ensure migrants' rights are not compromised8. Migrants face numerous challenges, from cultural adaptation to language barriers, which require strong institutions to help them overcome.

To achieve this, we can implement:

Employer Vetting: Comprehensive assessments ensure employers offer fair wages, secure accommodations, healthcare, and work conditions. This process would also screen for any forced labor risks.

Transparent Contracts: Provide employment contracts in migrants' languages, detailing roles, pay, benefits, and termination conditions, thwarting any bait-and-switch tactics.

Grievance Channels: Create avenues for migrants to voice concerns or lodge complaints against employers, ensuring a safe environment without retaliation threats.

Job Mobility: Decouple visas from specific employers. This flexibility empowers migrants to change jobs if they face any mistreatment.

Financial Training: Equip migrants with the knowledge to comprehend loans and manage finances, curtailing the risk of predatory lending.

Cultural Integration: Offer pre-arrival orientation covering labor rights, healthcare, workplace norms, and sociocultural dynamics, facilitating smoother transitions.

NGO Support: Engage NGOs to deliver essential services like legal aid, advocacy, and counseling, ensuring migrants have an independent support network.

By integrating these safeguards, ISAs can foster migration that enriches both migrants and the economies they join.

The Migration Market Potential

On the supply side, a potential market of 10-20 million migrants annually would move from LMICs to HICs if financing were available. Surveys by Gallup, Arab Barometer, and others reveal migration intentions ranging from 20-59% in low-income countries. With approximately 700 million adults in low-income countries, this indicates a willing migrant population of 140-413 million. According to the 2015 status quo scenario from the Population Division of the UN DESA, the working-age population in all developing regions is projected to witness an increase of over a billion individuals by 2050.

HICs face a substantial labor deficit, with the Boston Consulting Group (BCG) estimating 30 million open jobs in the thirty largest economies and a projection of 345 million working-age adults exiting the job market by 2050. This aligns with the Center for Global Development’s understanding of OECD models, which indicate sustaining current worker-to-retiree ratios will require HICs to have an influx of 400 million additional workers over the next 30 years, translating to over 15 million workers annually. When framed in GDP terms, addressing global population dynamics through migration can bridge the anticipated labor shortfall, potentially injecting $13 to $25 trillion into the global economy annually by mid-century.

Assuming a typical migration-based ISA costs €30,000 per person, then 10-20 million ISAs issued would require €300-600 billion in issuance annually. With repayment timescales over 10 to 20 years, the total outstanding ISA market could reach €3-12 trillion, comparable to the mortgage-backed securities market with $11 trillion outstanding9.

Pooling Loans into Asset-Backed Securities

The potential ISA migration market is vast, requiring large-scale solutions. Asset-backed securities (ABS) pool individual ISAs to create a securitized asset that could become a liquid market.

Idiosyncratic risks are reduced by aggregating thousands of individual ISAs into pooled securities. Investors in the ABS receive principal and interest payments from the underlying pool of ISAs, providing a stable return with understandable risks.

The ABS can be structured with seniority to appeal to different investor risk profiles. Senior tranches get priority on payments from the ISA pool, making them low-risk/lower return. Junior tranches assume more risk but offer higher potential yields.

Implementing a seniority structure paves the way for institutional entities to offer focused backing. Development Finance Institutions (DFIs) can bolster socially beneficial credit through credit enhancement, as evidenced by their involvement in green infrastructure ventures. If DFIs prioritize and incentivize ethical lending practices, it will cultivate an environment where ethical lending thrives, sidelining predatory tendencies.

When ISAs are pooled into an ABS, they can be bought and sold in secondary markets, which provides lenders with an exit strategy and increases the attractiveness of these instruments to a broader range of investors. Liquidity in a secondary market is necessary for the market to scale to meet rising migration financing needs.

At full scale, an expected market clearing return would be approximately a 1% premium above the appropriate government bond rate10. Hopefully, DFIs will accept lower returns given the high social impact. Their participation as anchor investors could help catalyze the growth of this market.

Net Present Value of Migration

To gauge the feasibility of a financing initiative, lenders look at the net present value (NPV) of how funds are used. If there is no value added, then lenders will not lend. Boiling down the intricate migration process to a mere calculation might seem overly simplistic, echoing some criticisms often levied against the finance sector. However, I aim to underscore the substantial forgone value and the costs of a corresponding missing market.

The calculation below is based on the expected earnings differential between the origin and destination countries and includes several assumptions:

Discount rate: 4%

OECD average annual salary: $53,400

Migrant Earnings Discount: 80% of the OECD average salary, amounting to $42,720

Origin country average annual salary: $2,720

Productivity growth and earning convergence rate: 2% annualized

Migration time cost: 2 years of lost earnings

Working career: 40 years

Taxes are omitted since their benefits are assumed to equate with the taxes paid11.

Under these assumptions, the NPV of migration for one individual, representing the present value of 40 years of excess OECD earnings at $40,000 p/a with 2% annual growth, is approximately $1 million. This significant value-add for the migrant implies a large zone of possible agreement for the ISA market.

Repayment Risks

The NPV omits two essential conditions: the fraction of borrowers that earn an income that facilitates ISA repayment and the ISA provider's capability to enforce the contract. Historically, ISAs have struggled in markets saturated with traditional student loans, primarily due to adverse selection12. Adverse selection refers to higher-risk individuals opting for a financial product, increasing average costs, and pricing out low-risk individuals who can use established alternatives.

However, the landscape is different for ISAs targeting migration and education. Even borrowers with promising future earnings lack financing options in LICs. Without adverse selection, the challenge shifts from discerning high-risk candidates to ensuring broad access to the opportunity.

Repayment evasion remains a concern, with tactics ranging from under-reporting income to unannounced relocations. Countries like Australia and New Zealand have grappled with this; migrants who procured education loans and later moved abroad evading repayments13. Some developing countries use employer-led repayment deductions, which are practical for short-term migrations but less so for longer durations or educational migrations. A collaborative approach, potentially involving destination country governments in income reporting, might be more effective14.

Neither governments nor free markets are singularly equipped to address these challenges due to the diverse strategies required and inherent limitations with enforcement. The solution won't be one-size-fits-all; each ISA provider will tailor strategies to their context. This could encompass rigorous screening, community-building, or ethical enforcement mechanisms. Emphasizing repayments as support for subsequent migrants, rather than mere obligations, can foster a sense of community and accountability. The framing and implementation of these structures will be crucial to ISAs' long-term viability.

Modeling the Migration Decision

Will ISAs increase the number of people deciding to migrate?

The following is based entirely on work from David McKenzie and Dean Yang.

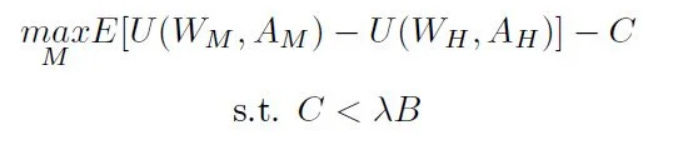

“Consider a potential migrant deciding between staying in their home country where they earn home wages WH and benefitting from amenities AH, or paying a cost C to go to another destination (either abroad or in a higher paying destination internally), where they face uncertain wages WM and amenities AM. Then migration will occur if the expected gain in utility from migrating exceeds the costs of migrating, and they can afford the costs of migrating. That is, the decision is migrate if:

Where B is wealth, and λ is how tightly liquidity constraints bind.”

Above, we calculated the NPV of migration, which is effectively the entire equation after max. The million dollars is above the cost, but we are constrained by the cost in the second line. Migrants don’t have access to wealth or borrowing to pay the cost now. Giving them access will allow them to pay that cost and increase migration.

Comparing ISA to Traditional Fixed Debt

Conveniently, David outlines five potential channels through which we can amplify migration. I'll use his framework to juxtapose ISAs with traditional debt and direct grants.

Change the ability of individuals to pay these costs - Multiple studies indicate that as wealth rises in LMICs, so does migration. I infer that easing borrowing constraints would produce a similar effect. The requisite funds exceed what philanthropy can offer. When juxtaposing ISAs with traditional debt, ISAs distinctly shine. They leverage the potential high returns from success without the inflexibility of fixed debt during failures.

Change how expectations are formed - If lenders make money, they will advertise. However, ISAs have a built-in mechanism to prevent over-promising, given the repayment is contingent on success. Due to the complexities of forbearance, traditional fixed debt presents ethical challenges, making it less efficient in filtering out marginal cases.

Change the risk and uncertainty involved - Here, ISAs outshine traditional debt. If the investment doesn't pan out, ISAs ensure no additional financial strain befalls the migrant.

Change the costs of migrating - I am uncertain if ISAs affect this either direction; a heftier initial funding amount might lead to a steeper repayment. Yet, this also heightens the lender's potential loss. Separately, destination countries might stipulate higher benchmarks for migrants, confident in the financial backing for requisite training programs; a potential positive spillover if these benchmarks are realistic and cause increased investments in human capital.

Change the wages and amenities at either home or abroad - This ties into the potential escalation in migration costs. As destination countries often favor skilled workers, ISAs can set a performance baseline transparently with a minimum income threshold.

In summary, ISAs are the primary solution for most financing needs. Given the sheer scale of the challenge and the diverse financial scenarios we must cater to ISAs, fixed debt, and philanthropy will all be necessary. ISAs encourage investment in human capital. At the same time, philanthropy plays a complementary role, stepping in to aid those who might need more than what ISAs offer. Meanwhile, fixed debt can be judiciously used when risks are well-contained, ensuring we don't burden the most vulnerable.

Addressing Political Issues

This essay won't delve into the complex politics of immigration or strategize on mobilizing political movements in various HICs for enhanced migration15. Yet, it's essential to recognize politics is associated with migration. Every political idea, including the establishment of an ISA market for migration, will inevitably face opposition.

Successful issuance of ISAs could serve as a significant impetus to garner political support. Here are a few points to consider:

Economic Advantages: ISAs are a tool to reduce labor shortages in HICs, spurring economic vitality and innovation. Emphasizing this can resonate with economic pragmatists across party lines.

Harmonized Interests: ISAs align the interests of lenders and borrowers, creating a win-win situation. This concept can resonate with pro-business conservatives who appreciate market-based solutions and liberals who advocate for social equity.

Promotion of Social Mobility: ISAs enable individuals from LMICs to pursue opportunities in HICs. This aligns with the ideals of social progressives who champion equality and opportunity.

Empowerment of Migrants: The flexibility of ISAs allows migrants to choose their career paths, which can be an appealing argument to liberals and libertarians who value individual freedom and self-determination.

Crucially, the perception of control over migration policies plays a significant role in public sentiment16. Governments garner public support for immigration by consistently enacting and implementing transparently beneficial policies for their citizens. When voters are confident that their government is managing immigration to align with their interests, they are more likely to endorse increased immigration, including providing refuge for those escaping adversities.

ISAs can contribute to this sense of control by providing a structured, transparent, and regulated mechanism for financing migration. By emphasizing these benefits and building a broad coalition of support, we can make strides toward the creation of a vibrant ISA market for migration, contributing to global economic growth and increased opportunities for individuals worldwide.

Current Pathways are Sufficient

HICs are acutely aware of the demographic shifts underway and have accordingly established avenues for migrants across the skill spectrum to enter their territories. However, these pathways are often established within complex bureaucratic frameworks and are laden with intricate rules and procedures. This complexity, coupled with the asymmetry of information, often leaves potential migrants overwhelmed and unsure of how to navigate these routes successfully. The challenge isn't just to have pathways but to make them navigable.

Addressing this requires an efficient ecosystem to bridge the information gap. Such a system would serve a dual role. On the one hand, it would act as a conduit for education and skill-building for potential migrants, helping them align their abilities with the host country's requirements. On the other hand, it would serve as a communication bridge between the migrants and the government, ensuring that the migration pathways are understandable and accessible.

A well-structured ecosystem could also provide crucial evidence of these migration pathways' benefits to the destination country. This would help foster trust and collaboration between the migrants, the system operators, and the government, further facilitating the migration process.

However, maintaining such a complex infrastructure would necessitate substantial financing. This is where the ISA market plays a pivotal role. The sizeable ISA market could provide the necessary funds to maintain this infrastructure, thereby contributing to the smooth operation of the migration process. By offering a viable financial solution, ISAs could make the migration pathways more transparent, efficient, and beneficial for all stakeholders involved.

A Pilot Program

ISAs aren’t just theoretical solutions for migration. The success of Malengo, where I invested $3.4 million, is a testament. It is facilitating the journey of 120 Ugandan students to Germany for higher education and potential roles in the German workforce.

The contracts for these ISAs have been signed and all 120 of these students are already studying, working, and living in Germany. The legal counsel involved in this initiative has expressed confidence in the solidity of these contractual agreements. The nature of ISAs17 ensures that the obligations are clear and enforceable, providing a robust framework for this innovative approach to financing migration.

The students involved have voiced a strong desire to fulfill their repayment obligations, not merely to clear their debts but to ensure that future students have the same opportunities they've been given. This sense of responsibility and commitment among the borrowers is a positive indicator of the viability of the ISA model in this context.

Moreover, the Ugandan and German governments have responded positively to this initiative. This is a promising sign, indicating that there's potential for similar programs to be implemented on a larger scale without an anticipated government backlash.

Soon, I will present a detailed review of my model for Malengo. My analysis covers contract terms and external factors that could impact its success. I'll present a sensitivity analysis to determine how changes in these factors might affect outcomes, providing a clearer picture of Malengo's resilience in different scenarios.

The vast potential benefits from ISAs provide considerable leeway in contract formulation. Initial contracts might have parameters leading to returns that deviate from market averages. Yet, the inherent flexibility allows for subsequent adjustments. I'm optimistic that, over time, contract terms will align with market rates, reflecting the associated repayment risks. Put simply, if repayment risks are significant, the repayment caps will be adapted accordingly18.

This pilot project serves as a tangible example of how ISAs can facilitate migration, providing individuals from LMICs with opportunities for higher education and employment in HICs. The positive initial outcomes suggest that ISAs can indeed be a viable solution to address the barriers to migration, thereby unlocking the massive potential benefits for individuals and economies alike.

Opportunities Should Not Be Constrained By Birthplace

ISAs could pave the way for millions of potential migrants to access the funds needed to seize opportunities in destination countries that align with their skills and aspirations.

Realizing that potential would lead to substantial economic advancement. Projections suggest that integrating 400 million workers into HIC economies could generate an additional $20 trillion in economic output by 2050. Economic growth enhances the living standards and income potential of the migrants and the destinations' economies.

However, transforming this immense potential into reality demands joint efforts across various sectors. Financial institutions are responsible for creating and distributing ISA products that are ethically sound and respect the rights of migrants. Securitizing these products is also crucial as it attracts investment from the capital market.

International organizations set protective norms and provide technical assistance to nurture the emergence of the market. International agencies could define the terms of ethical lending practices. Development banks can give ethical ISAs beneficial lending terms, which create norms that protect the interests of borrowers, and provide the necessary funding to initiate and sustain the market.

Realizing this vast potential will require commitment, substantial investment, and a visionary approach from all stakeholders involved. Yet, the social and economic benefits that can be attained make this pursuit deeply rewarding. Moral and economic reasoning dictates that geographical borders should not confine opportunities. Advancing towards a fully operational ISA migration financing market brings us closer to achieving this aspiration.

I owe my gratitude to Ruchir Agarwal, Ryan Briggs, Johann Harnoss, Johannes Haushofer, David McKenzie, Karl Rohe, and Jasnam Sidhu, whose discerning commentary aided in refining the ideas presented here.

The facts and figures regarding the quantity of migration are based on “A Good Industry and an Industry for Good” by Rebekah Smith and Zuzana Cepla. In addition, the framework for ethical labor migration is inspired by the work.

Market sizes in trillions: Credit card: 4.3 Mortgage: 11.7 Autos: 2.4

This source has the most markets in one spot, which I cross-checked with other sources to ensure they are valid. https://newsroom.transunion.com/q4-2022-ciir/

The cap is a non-obvious solution to the equity demanded by those with the highest incomes post facto. It is unlikely that the lending provides uncapped benefits, so it would be unfair to have uncapped obligations from the ultra-successful.

The history of SG gives me confidence in the social structure of a pro-social ISA network being built. For example, SG reports that ISAs are opt-in and about two-thirds of students take this option. "In the mid-90s tuition fees had to be introduced at the University of Witten/Herdecke. As a result, the students developed the ISA in order not to make the decision to study dependent on the financial background. Rather, the decisive criteria should be professional and personal aptitude and motivation. Since then, the ISA has been very successful: in Witten, two out of three students use it."

Fun fact, ISAs are also exciting in the space of encouraging elites to go into the public good rather than go into the most lucrative options after expensive university or graduate programs. https://law.stanford.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/ISA-Student-FAQ-.pdf

The original book on ISA: https://www.amazon.com/Investing-Human-Capital-Markets-Approach/dp/0521828406

My favorite framework for ISA is from Better Future Forward who drive US policy nowadays: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6109747eac138122e5b8603e/t/62bb46982e6dd66d509fa94b/1656440519345/Building+An+Equitable+Student+Finance+System_June+2022.pdf

My favorite champion has been LaMP and they have begun hosting the forum for responsible recruitment: https://gfrr.org/

This section draws directly from https://lampforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/lamp_report_mobility-industry.pdf

Total issuance is not my favorite metric. However, we must choose some measurements.

For example, SOFR + 100 resetting quarterly would be the contract specification.

I also omit a wide range of benefits, principally the increased opportunity for the migrant’s descendants. If I get enough demand, I can elaborate.

I have received pushback with this assessment, I would be happy to learn empirical strategies for estimating why ISAs aren’t more popular.

See the first paragraph of section 8

Organizations such as https://www.forteglobal.com/ are working with governments to build this infrastructure as we speak.

Due to popular demand, I add this footnote on brain drain. Due to its complexity, I'll address the topic of brain drain in a forthcoming essay. My stance is influenced by Amartya Sen's perspective on freedoms and capabilities. Limiting people's mobility across borders hampers inherent rights and human potential. In development economics, it's crucial to remember that the focus should be on "people, not places." Restricting movement contradicts this core principle.

I struggle to provide only a single reference and line of argument here. For simplicity, paper length treatment: https://osf.io/wt74y/, Book length treatment pending: https://alexanderkustov.org/book/

They are based on the ISAs issued by SG and Chancen, which include proof of income via German tax forms.

In analogous markets, repayments typically approximate 30% of the NPV. For instance, in small business loans, lenders commonly target loan repayments to constitute 15-35% of a business's operational cash flow, ensuring the business retains the bulk of enhanced cash flows. Similarly, venture debt lending practices often dictate that interest payments cover 30-40% of the total capital invested over the loan's duration. In contrast, current contracts under Malengo are structured to capture a mere 5% of the borrower's projected NPV.